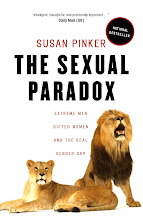

Some people collect elephant figurines, cranberry glass, first editions or vintage sports cars. I collect weird facts, especially ones that differentiate the two sexes, though to be frank, I never decided to amass these bits and pieces. They just drift towards me as if equipped with their own magnetic charges, often via email messages from acquaintances and virtual strangers. Sometimes the facts are actually handed to me in person. That’s what happened yesterday as I sipped a tall glass of iced coffee in Em Café, in the Mile End on a balmy spring afternoon in Montreal. The journalist, Éveline, who was writing about me in a French psychology magazine, flounced in, as blond and breezy as the day, and spotted me right away, having seen me give a public lecture on the Sexual Paradox at a library (

http://www.susanpinker.com/book.html) just a few days before. Even before we shook hands she proferred a ragged clipping from that morning’s French newspaper, le Devoir, entitled: L’Oestrogène, l’arme secrète des femmes (Estrogen, Women’s Secret Weapon):

http://www.ledevoir.com/2009/05/12/249980.html.

The clipping described the latest research of Dr. Maya Saleh and her team of microbiologists at McGill just published in yesterday’s PNAS (

http://www.pnas.org/) which shows how estrogen offers a measure of protection against illness that men just don’t have. Apparently, estrogen blocks production of an enzyme called Caspase-12. Caspase-12 makes us weaker—more vulnerable to marauding infections by preventing inflammation, the body’s way of telling an invader to back off. Without this chemical shield provided by estrogen, males are more likely to get sick, one reason why men everywhere have a higher rate of just about every chronic and infectious illness around, why they’re 70% more likely than women to die from hospital based infections like C-difficile, and why, despite dying with the most toys, they tend to die a whole lot younger. Yale anthropologist, Richard Bribiescas summed up the male lifespan as Stud, Dud, Thud. But that was before hormone replacement therapy for guys. Dr. Saleh said that dosing men regularly with estrogen instead of multivitamins might work as prevention, but might not be such a great plan because then their bodies might start to acquire female features. Now that’s what I call a trade-off, exchanging a few inches of biceps and body hair for a few extra years of life. Any takers?

Meanwhile, last week an email mysteriously arrived from a guy named Patrick, who for the last few days has been dosing my inbox regularly with tidbits like this one: Without estrogen, the brain doesn’t process sounds too well. Apparently, estrogen tells the brain to lay down the neurons that make us highly sensitive to sounds (

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/05/090505174543.html). The researcher, Raphael Pinaud, extrapolated from his findings from birds and how they use songs to communicate with each other. Apparently, estrogen is not why the caged bird sings, but why she’s very likely to remember the song. Now, that’s what I call a secret weapon.

Why the Good Die Young

Why the Good Die Young