Why the Good Die Young

Why the Good Die Young

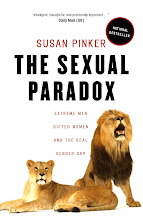

The suicide of former South Korean president, Roh Moo-hyun, earlier this week was a tragic reminder of the all too high suicide rate, especially among extreme male high achievers living in industrialized nations. If there was full acknowledgment of this well- documented vulnerability in men, you’d think assistance would be close at hand. Yet men like Mr. Roh, who have made genuine contributions to society, too often take their lives rather than lose face or seek help for depression or despair. Mr. Roh had spent the first part of his career as a human rights lawyer and had committed his second act to public service and clean government in South Korea. But according to a suicide note, he couldn’t face the “shame” of a political smear campaign, and after a period of insomnia and loss of appetite—both typical symptoms of clinical depression—he jumped off a cliff. Hence, no third act. Like 10% of male leaders in democratic countries (and 85% of male rulers outside democracies) Mr. Roh’s ended his political career in a casket. Given the odds, it takes a an extreme personality—one not afraid of mortal risks—to enter public life. An insouciance about one’s future, combined with single-mindedness—is also why a climber named Frank Ziebarth died after an ascent to Everest this week. He was a purist who wanted to scale the death zone of the summit without the “help” of oxygen. Like David Foster Wallace, who Los Angeles Times

No comments:

Post a Comment